This will be a three-part series, this part detailing the mythic origins of Athens and the earliest history of the city, until the conclusion of the second Greco-Persian war. The second will deal with the Delian League, the most famous personages of Athens of that period, and the Peloponnesian wars, the third will cover the political decline and cultural flowering of Athens, its relations to Macedon, and finally its history under Rome.

CHAPTERS:

Myth and Scenery

Synœcism and the Areopagus [~800-~600]

Crisis and Draco [~620-594]

The Political Reformers [594-507]

i. Solon

ii. Pisistratus

iii. CleisthenesGræco-Persian Wars [499-478]

Myth and Scenery

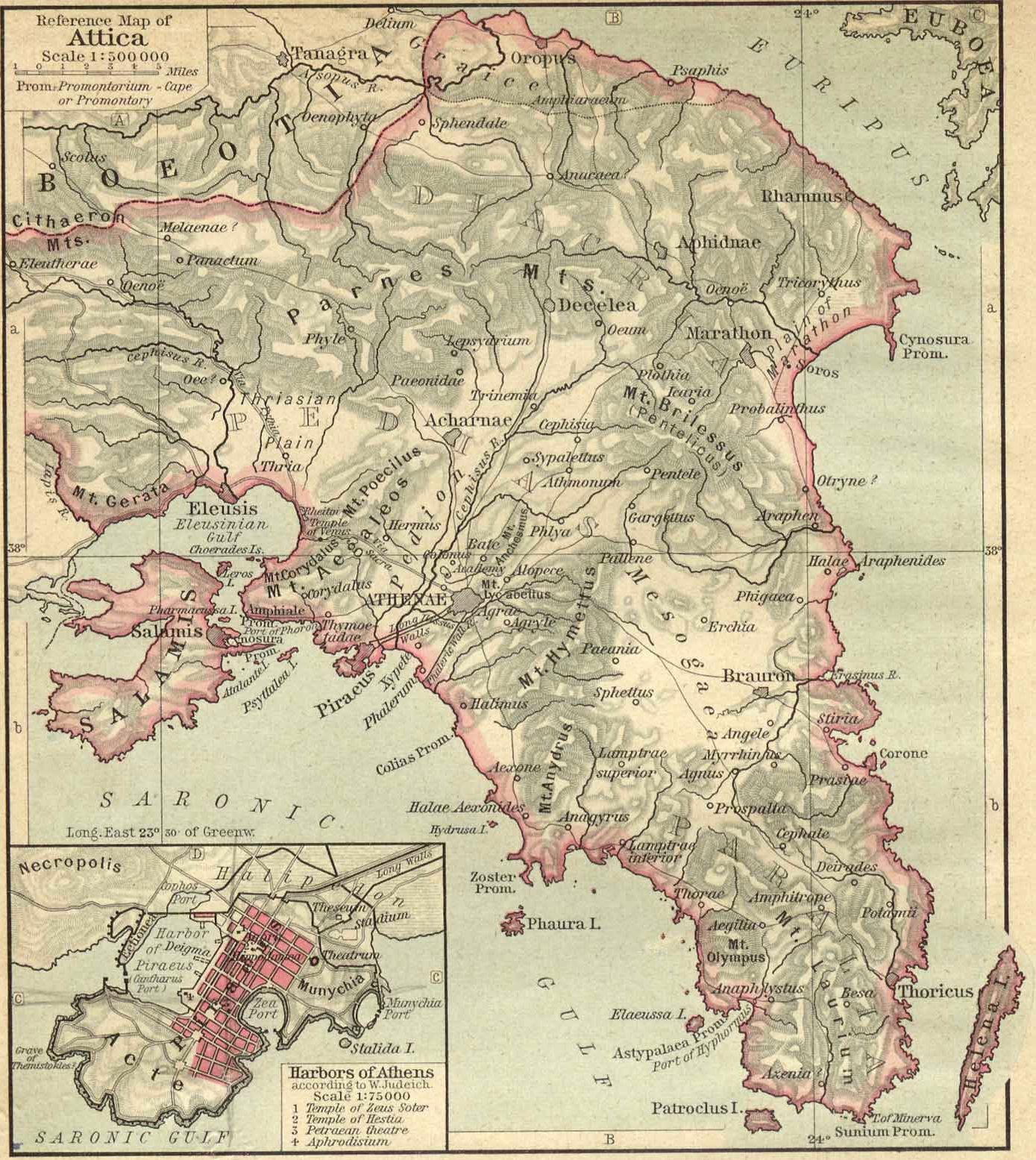

Although not a major Mycenaean center, nor a significant city in the time of Homer, Athens would leave perhaps the most profound mark of all the cities of Greece on the subsequent history of the Hellenic world as well as our own. Nestled in south-central Attica, the peninsula situated north-east of and connecting to the Peloponnese, it juts into the Aegean and points into the direction of the Cyclades. North of it is the long island of Eubœa, shielding Attica to the east as well as wet Bœotia (home to Thebes) to the west, Bœotia itself being the land connecting Attica to all Greece north of it. South lies the aforementioned Peloponnesus, connected to Attica and Bœotia by the Isthmus of Corinth, two Dorian cities lie at the entry to the Peloponnesus, nearer to Athens of these is Megara, with whom she had an ancient dispute over the island of Salamis, while farther south at the very entry to the Peloponnese lies Corinth, with whom Athens shared in all likelihood the most similarities of any other Greek polis, and so she was one of her most enduring rivals.

Herodotus, Plutarch, and Ovid, among others, describe the naming of the city as having occurred through a contest between Poseidon and Athena. The two deities gave the city a gift each, the former bequeathed the city a saltwater spring upon striking the ground with his trident, while Athena plants (the first) olive tree on the Acropolis [lit. high-city]. Then either the Olympians or the serpentine first king of Athens, Cecrops, judge Athena’s gift to be greater and she is made the patroness of the city.

The identity of the mythical first king of Athens is not certain, Cecrops being often mentioned, while the first king prior to Athens’ self-invented and revisited history was another autochthonous12 being, Erichthonius, born of Hapheaestus’s seed and reared in the Earth itself, later adopted by Athena, and represented as a snake beside her feet.

From Cecrops the lineage goes through Cranaus, Amphictyon, Erichthonius

(in this chronology a succeeding monarch), Pandion I, Erechtheus, Cecrops II, Pandion II, Aegeus, and to his son, Theseus. With Theseus we come upon the story of the Minotaur. The city of Athens was required to send fourteen youths, seven male-female pairs, to Crete every nine years as tribute, to be sacrificed to the bull-headed monster born of Pasiphaë, Queen of Crete, and the Cretan Bull.

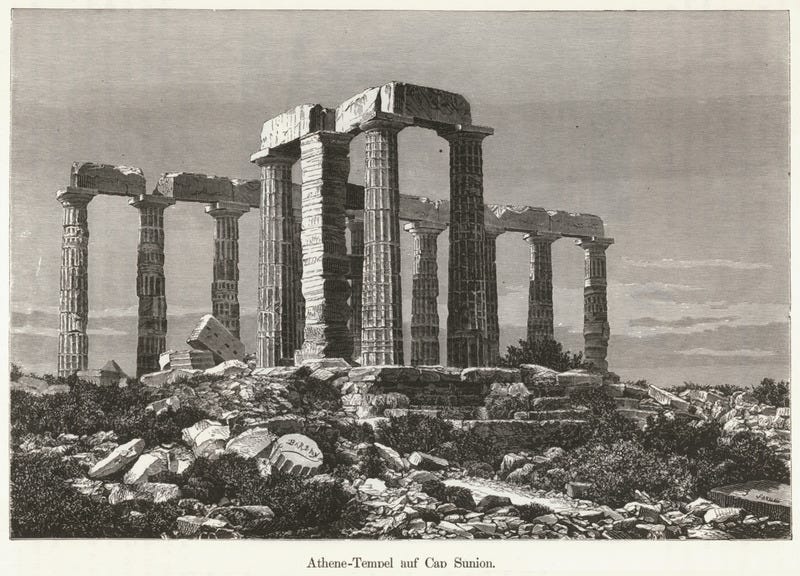

Theseus killed the monster and freed his city of her vassalage to Crete, but he neglected to change his sails from the draped black ones, which his father Aegeus took to mean his son’s death, and he leapt to his death from Cape Sounion into the sea, thereafter the sea being named the Aegean.

Whether or not this story implies a vassalage of Athens to the Dorian, or perhaps even the Minoan Cretans in the distant past is often discussed. As for Theseus, he continued with his own heroic undertakings until he was thrown off a cliff, like his father. The King Lycomedes pushed him to his death on the island of Scyros when Theseus had lost popularity back in Athens.

From Theseus we go onto Menestheus, Demophon, Oxyntes, Apheidas, and Thymoetes. Here ends the Erechtheid dynasty, followed by the Melanthids, their first monarch Melanthus was King of Pylos in the Peloponnesus but he was driven out by the Dorian invasion, Thymoestes resigned the crown to him. Following Melanthus then came Codrus, who repelled the Dorian invasion into Attica and came to be known as the greatest monarch of the city. So great, in fact, that monarchy was in multiple accounts ended precisely because the Athenians judged that Codrus was the greatest king they could have had, and after him the institution of monarchy would never reach the heights that he brought it up to. And so ended the ancient regal period of Athens.

Synœcism and the Areopagus

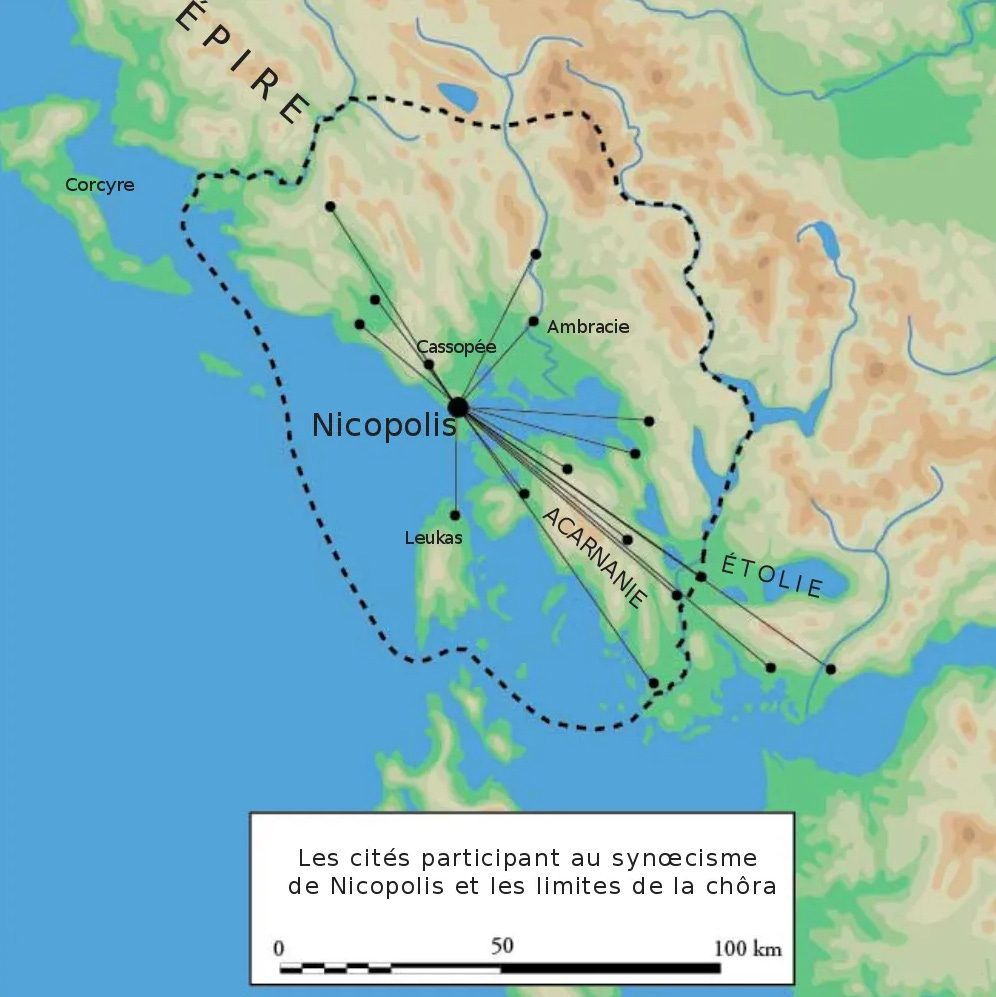

The process by which this so characteristically Greek form of government, that of the polis, came about, is called synœcism. Whereby small towns and settlements gradually found a center of gravity and coalesced into greater settlements until we get the first true cities in Greece after the depopulation of Minoan and Mycenaean centers. Theseus, dated to be a contemporary to the figures of the Iliad, in Athenian myth had been credited with accomplishing the Attican synœcism.

This is unlikely, as the Homeric hymns speak of a king at Eleusis as late as the 7th century. The process of synoecism must have been finalized much later for Attica than that period credited to Theseus, contemporary with the Trojan war. The towns of Hymettus, Pentelicus, Parnes, Piraeus, and others coalesced into one center of gravity, and the landowners from these became the ruling aristocracy of a centralized Attica, the Eupatrids.

The Eupatrid oligarchs—i.e., the well-born ruling few—continued to govern Attica for almost five centuries. Under their rule the population was divided into three political ranks: the hippes, or knights, who owned horses and could serve as cavalry; the zeugitai, who owned a yoke of oxen and could equip themselves to fight as hoplites or heavy-armed troops; and the thetes, hired laborers who fought as light-armed infantry. Only the first two were accounted citizens; and only the knights could serve as archons, judges, or priests. After completing their term of office the archons, if no scandal had tarnished them, became automatically and for life members of the boule or Council that met in the cool of the evening on the Areopagus, or Ares’ hill, chose the archons, and ruled the state. Even under the monarchy this Senate of the Areopagus had limited the authority of the king; now, under the oligarchy, it was as supreme as its counterpart in Rome.

—Will Durant, The Life of Greece, Ch.V, Athens

The comparison to Rome is very apt, given that after the expulsion of the Tarquins, the Senate was an exclusively aristocratic body, much like the Areopagus of Athens. Senatus Populusque Romanum meaning, the Senate (the nobility) and the People (the tribunate) of Rome.

Crisis and Draco

The poorest of the Athenians—named the georgoi for they lived in the arid and infertile hills of Attica (while the rich lived in the flat plains and the mercantile classes near the coast)—owned small tracts of land, but primogeniture not being a feature of Greek familial life, the holdings were divided further and further with each successive generation. Many of these peasants sold the land and moved to Athens or the surrounding villages to become artisans or traders. Others became tenant tillers of the Eupatrid estates who were paid in a fraction of the produce, grown on land formerly belonging to them or their ancestors.

Debt brought about serfdom, and those serfs upon failure to satisfy their creditors were often sold into slavery along with their families. In addition to this, foreign slaves and foreign markets reduced the economic power of these farmers even further. Many starved, and poverty and hunger became so great that war was counted a blessing, as more land might be won and there would be less mouths to feed. As a consequence of this, any manual labor was associated with tenant poverty, and therefore inappropriate for any man of higher station.

For a time men hoped that the legislation of Draco would remedy these evils. About 620 this thesmothete, or lawmaker, was commissioned to codify, and for the first time to put into writing, a system of laws that would restore order in Attica. So far as we know, the essential advances of his code were a moderate extension, among the newly rich, of eligibility to the archonship, and the replacement of feud vengeance with law: here after the Senate of the Areopagus was to try all cases of homicide. The law was a basic and progressive change; but to enforce it, indeed to persuade vengeful men to accept it as more certain and severe than their own revenge, he attached to his laws penalties so drastic that after most of his legislation had been superseded by Solon’s he was remembered for his punishments rather than his laws.

—Will Durant, The Life of Greece, Ch.V, Athens

Pertaining to the severity of punishment under this new and first constitution

of Athens, upon being asked as to the reason for it being so harsh, Draco said:

And Draco himself, they say, being asked why he made death the penalty for most offences, replied that in his opinion the lesser ones deserved it, and for the greater ones no heavier penalty could be found.

— Plutarch, Life of Solon, 17.2

This constitution seems to only have delayed the outbreak of what, if not for another series of figures, would have been an Attican social war. Draco’s legislature did not survive long after him, he himself being exiled to Aegina, in the Saronic gulf, wherein he lived out the rest of his life.

The Political Reformers

From the 620’s when Draco’s legislature had been enacted, until the early 6th Century in Athens, the problems of Draco’s time had continued, and the city-politic had been effectively in gridlock. The aforementioned social war, which would entail the nobles, the middle class, and the peasants (or the plains, coastal, and hills factions) was still a latent possibility. It would take three generations of democratizing statesmen for Athens to go from a second-rate city to the foremost power in Greece, that would take place under one of the most delicate balances of power between the aristocrats and the freemen.

Solon

Descended from King Codrus as well as Poseidon, his mother the cousin to the mother of Pisistratus, there were few in Athens of blood eqully Eupatrid. In his youth he participated in the trends of his times, writing poetry, singing of pan-Hellenic friendship, or advocating the conquest of Salamis. It’s been said that his poetry worsened while his moral fiber increased as he aged.

In 594 representatives of the middle classes asked him to accept election as Eponymous Archon, but also encouraged him to take up dictatorial powers under the legitimacy of the office. He was empowered to establish a new constitution and restore societal stability.

It was the Solonian Reforms which brought Athens into the stream of history, not as a drifting raft but now a vessel to be steered and commandeered. Solon had brought every adult male citizen into political life. He opened up an assembly of Athenian citizens, which from now on would be the centre of all Athenian politics.

A minimum of 6,000 citizens had to be present before a vote could take place, it would take the form of a public show of hands, each and every citizen would know how every other citizen voted, strong political opinions were practically seen as a civic duty, seldom was there neutrality, and even rarer was apathy. Separate from the Areopagus, Solon also had established the Boule, a council which deliberated on what exact issues would go before the Assembly for a vote.3 He then divided the citizenry of Athens into four classes, based on the amount of revenue their property was capable of producing:

Pentakosiomedimnoi - eligible to serve as the nine Archons, as members of the Areopagus (as former Archons), the council of 400 (the Boule), and as strategoi, produced over 400 medminoi (volume of cereal, grain, or equivalent) a year, the aristocrats of Athens.

Hippeis - men who produced 300 medminoi , income was high enough to support owning a horse, hence these men often made up the cavalry.

Zeugitai - men who produced 200 medminoi a year, enough so as to own a hoplite’s armor and serve as infantry.

Thetes - lowest rung, produced less than 200 medminoi a year, would work for wages.

Each of the four classes elected 100 men to the Boule (the council of 400). Given one had to be at least moderately wealthy to be included among the Zeugitai and above, the state was nonetheless heavily aristocratic, 75% of elected representatives of the Boule would have represented either the pentakoisiomedimnoi, hippeis, or zeugitai. The Areopagus after Solon’s reforms was no longer responsible for electing the Archons. That would be decided on by the people of the four classes in a public vote. Ten candidates would be chosen to represent each class by an internal election, then out of the forty candidates assembled, nine would be appointed to be Archons by lottery. The Athenians would cite piety as to their reasoning in this.

In 572, aged sixty-six, Solon resigned after service as Archon Eponymous for twenty-two years. Having the officials of the city swear an oath to guard his laws unchanged for ten years, he set out traveling. First to Egypt, where he studied history, later to Cyprus where he drafted a law-code for the Cypriots, who in his honor named the city thereafter Soli. In his time abroad having made the association of King Croesus, who would come to be dethroned by Cyrus the Great in 546. In this time likely also corresponding with his friend, the first philosopher, Thales of Miletus. Solon would return to Athens to die there, but not before seeing his constitution trampled on, when his cousin, Pisistratus, made himself Tyrant of Athens.

Pisistratus

During a meeting of the Ekklesia (the assembly), Pisistratus displayed a wound, claiming it had been inflicted on him by the enemies of the people, and asked to be granted a bodyguard.

Solon protested. Nonetheless his cousin was given fifty men, yet he increased the size to four-hundred. He seized the Acropolis. Solon then declared to the Athenians that “each of you, individually, walketh with the tread of a fox, but collectively, ye are geese.” He hung up his shield outside his door, showing his resignation from politics, and thereafter wrote poetry until his death.

The plains and coastal factions, both wealthy, temporarily united to oust the dictator in 556. Pisistratus however made a deal with the coastal forces, and persuaded them to oppose him no longer. In addition to this, Pisistratus had arranged for his triumphant return into the city to be ordained by the gods, for he had a woman dressed up as Athena, and seated her proudly in a chariot, she lead his forces back into the city.

The people of the city, fully persuaded that the woman was the veritable goddess, prostrated themselves before her, and received Pisistratus back.

—Herodotus, i, 60; Athenaeus, xiii, 89

In 549, at the instigation of the coastal faction, he’d meet his second exile, but in 546 he returned once again, defeated opposing troops, and maintained his dictatorship for nineteen years. Surprisingly, he forgave most of his enemies, banished those who’d never bend to his will, he improved the army and the fleet, yet kept the city out of conflict. Although in blatant violation of his cousin’s legislature, he did not repeal nor remove anything pertaining to it. State-owned land had been given to the poor, and the land of banished aristocrats given to them as well, idle Athenians were likewise put to work on the soil, the problems of Draco’s generation virtually gone.

Commerce, industry, art, all flourished under his enlightened despotism.

New temples and beautified public structures had been erected in stone and marble, showing the city to the outside Greek world, he established the Panathenaic games. Pisistratus had established a trend, that of aristocrats coming to power by means of condemning their own, supplicating the poor, and cooperating with the middle-classes. Thereafter the dictator would abolish private debts, finance large public projects, flaunt and give away his wealth, and buildup a coalition of the ambitious and young. A pattern that would continue until Julius Caesar in Rome, a sea and five centuries away.

Cleisthenes

Pisistratus died in 527, passing down his rule to his son, Hippias. He had continued the policies of his father and tried his best at emulating him, the younger brother meanwhile, Hipparchus, was devoted to poetry and love. The demise of Pisistratus's dynasty coming about apparently through a homosexual love-fued.

Aristogeiton, a man of middle age, had won the love of the young Harmodius […] But Hipparchus […] also solicited the lad’s love. When Aristogeiton heard of this he resolved to kill Hipparchus and at the same time, in self-protection, to overthrow the tyranny. Harmodius and others joined him in the conspiracy (514). They murdered Hipparchus as he was arranging the Panathenaic procession, but Hippias eluded them and had them slain.

—Will Durant, The Life of Greece, Ch.V, Athens

Hippias, perhaps knowing only how to emulate and not how to rule, was struck by this attempted overthrow to such an extent where his rule now drastically changed character, and became a regime of suppression. Harmodius and Aristogeiton, meanwhile, were transformed from men embittered in a private affair against a statesman’s relative, into tyrant-slayers in the public perception.

In Delphi, the Alcaemonids, exiled by Pisistratus, raised an army and marched on Athens during this time, attempting to reestablish aristocratic rule at the sight of democratic turbulence. At the same time, the Alcaemonids bribed the Pythian Oracle to command the Spartans who consulted her that their state must overthrow the regime of Hippias at Athens. And so, Hippias resisted the Alcaemonids successfully, but when the Spartans came to their aid, the tyrant was overwhelmed. His children were captured, and as the price for their safety, Hippias abdicated and went into exile (510). The Alcaemonids lead by Cleisthenes, entered Athens, and the other banished Eupatrids with them.

Whereupon the aristocrats returned to Athens after their banishment by Pisistratus, they held an election for the office of Archon Eponymous. Cleisthenes was a candidate, but the victory went to Isagoras, and so, Cleisthenes rose in revolt, overthrew Isagoras, and established a social dictatorship of the very same nature that he and his relatives had overthrown.

The Spartans attempted to invade Athens again, seeking to restore the aristocrats to power, but the Athenians resisted fiercely, and Cleisthenes, the Alcaemonid, established democracy in 507.

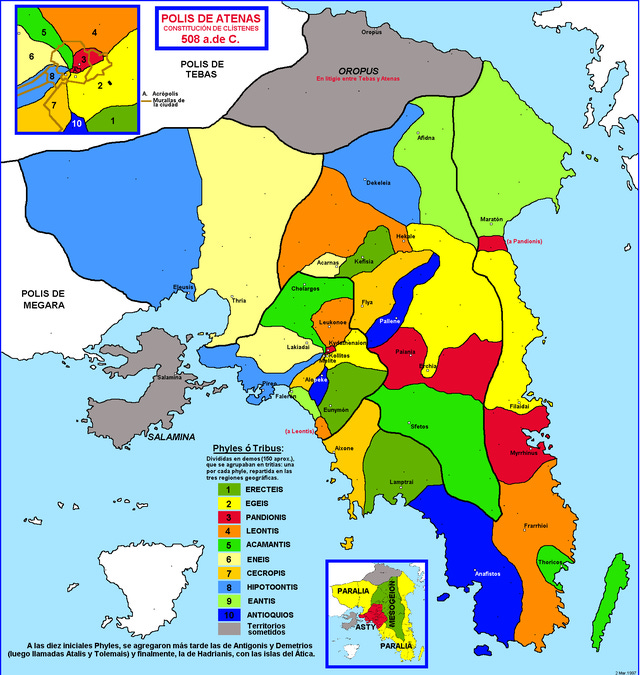

He replaced the old kinship classification of four tribes and 360 clans, which the aristocrats took full advantage of to leverage more votes, with a territorial division of ten tribes, and to prevent interests coalescing in these tribes through their location, as with the former factions of the coast, plains, and hills, each tribe included demes with an equal amount of land in all three. New religious rites and rituals were conducted for the inauguration of the ten tribes, as the previous four already had their own. Foreign freemen became citizens of the demes in which they resided, and the amount of voters had been doubled. It wouldn’t take a political genius to deduce to whom these voters of foreign-ancestry would now pledge their support towards.

He introduced the mechanism of ostracism, wherein every year votes would be held for the banishment of individuals from the city, and only the names which were repeated 6,000 times or more (written on broken pottery-shards) would render these persons expelled from the city for a period of ten years. This measure, or a similar one, seems to have existed also in Megara, Argos, and Syracuse.

Each new tribe contributed fifty members of the Council of 501, which replaced Solon’s Council of 400. Each of the councillors chosen by lot and for a term of one year. All citizens above the age of thirty who had not served two terms already were eligible to be chosen. A full meeting of the Assembly in light of the new citizens would now equal 30,000 men.

The political change in franchise and development preceding the age of Pericles had now been completed. The timing being fortunate likewise, for were the Athenians to remain disorganized for just a decade longer, Marathon, and subsequently all Greece, stood to be lost to the Orient.

Græco-Persian Wars

If the Solonian reforms were what first gave Athens an inward destiny and a direction for the city as to her future accomplishments, her field of extension, then the Græco-Persian wars were what propelled that “destiny” from among the abounding city-states into the world-renowned excellency that it would become.

In 499, the Ionian city-states littering the western coast of Asia Minor rose in revolt against the Achæmenid Persians, the background of this rebellion best explained in this video:

These city-states of Ionia first came under the control of Croesus’ Lydia around two generations prior, and Lydia was subsequently conquered by the Persians. This Ionian Revolt lasted between 499 and 493, supported by Athens and Eretria, likewise Ionian. The revolt was put down, but Darius vowed to take revenge on the two cities, as well as having motives of conquest. As Hippias, back in 506, had offered the Persian Satrap at Sardis Attica already after fleeing Athens, and the land-conquests of the Achaemenids in the West ended at Macedon, the Persians were already well familiarized with this land.

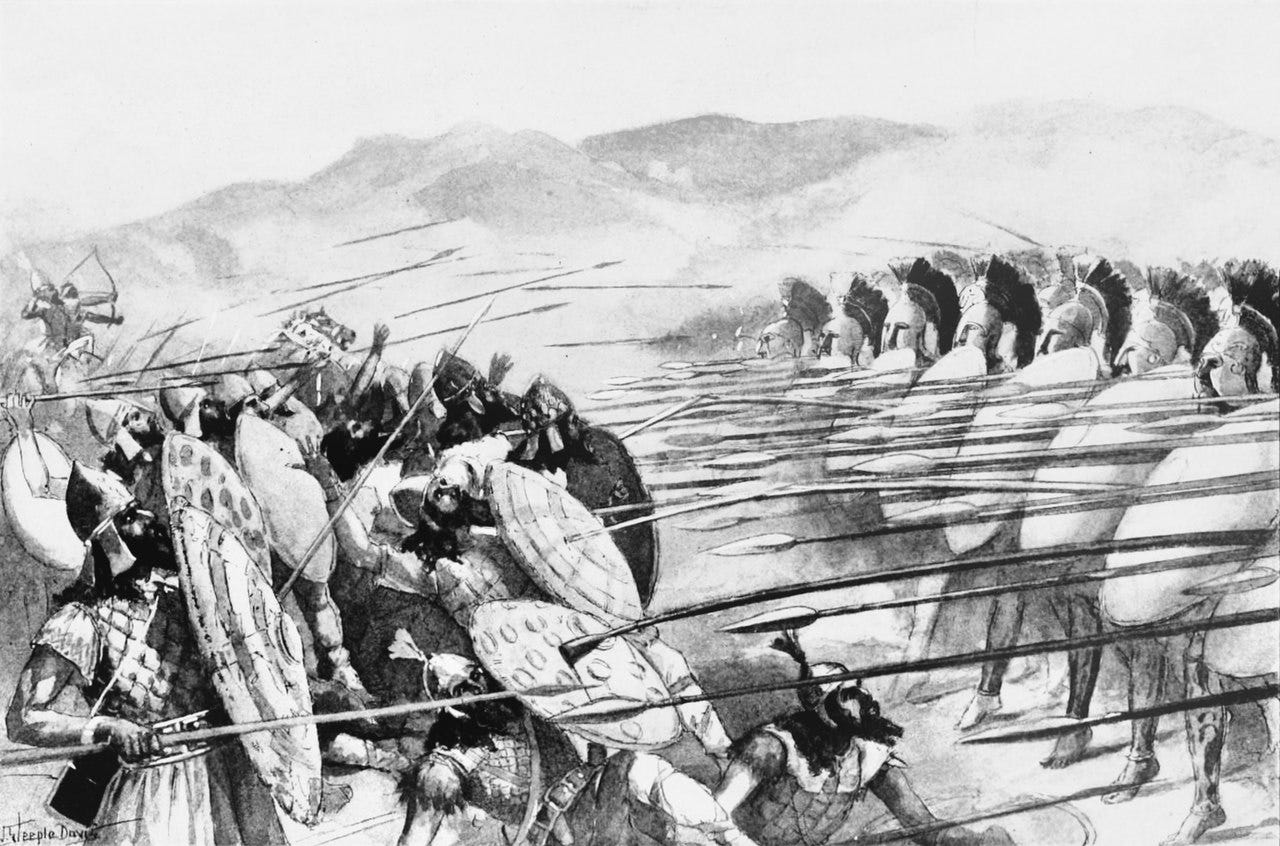

Darius the Great convened and sought to punish the two cities. The Persians landed in Attica in 490, after subduing the Cyclades and Eubœa, on the shores of Marathon they landed and were defeated by mostly Athenian but also Eretrian forces, the army lead by the Polemarch Callimachus, and under him ten Athenian strategoi, the significant ones among them being Themistocles, Aristides, Militiades (father of Cimon), and Xanthippus (father of Pericles). Militiades from the beginning having advocated for a direct confrontation with the Persian forces as they were to disembark from their ships, under his strategy the Greeks beat the Persians while outnumbered, the victory at Marathon in large part being creditable to him.

The defeated Persians then attempted to take Athens by sailing around the peninsula of Attica, wishing to bypass the exhausted army at Marathon, but the Athenians marched as fast as they could, for forty kilometers, in full armor, from Marathon to Athens, in time enough for the Persian fleet to spot them, which upon seeing the Athenians decided to retreat4. Athens had repelled the first Persian invasion of Greece, and won immense prestige.

During the ten-year gap between the first and second Persian invasions of Greece (490 and 480 B.C.) the great Militiades had been imprisoned by his countrymen on shallow accusations (on account of a failed military expedition on his part) and died of illness shortly thereafter, aside from this self-inflicted blunder, however, Athens would rise to higher and higher prominence. Two men, earlier mentioned veteran strategoi of the first Athenian war with Persia, would rise to the front of Athenian politics. The aristocratic and just Aristides, and the crafty champion of the lower classes, Themistocles.

In 483, in south-eastern Attica, great quantities of silver would be discovered in the Athenian mines of Laurion. One major contention between Aristides and Themistocles had been whether to build up the Athenian army or the navy, Aristides in support of the former and Themistocles the latter (for the army is the domain of trained aristocrats, supporting their own equipment, while the navy is that of the middle-classes utilizing state-owned vessels.)5

On this account Themistocles proposed investing the silver into the Athenian fleet while Aristides sought to distribute the silver equally among all Athenian citizens. The support for both camps seemed equal, so Themistocles waited until the annual ostracism vote would occur. Aristides got the most votes and was exiled from Athens, and Themistocles was free to invest the silver into the Athenian fleet.

In 481 the Greeks found out about Xerxes’s plan to invade and continue his father’s mission, now seemingly to take all of Greece instead of merely punishing Athens and Eretria. The poleis of Greece that set themselves in opposition to Persia coalesced then around the two dominant city-states that resisted the Achaemenids most; Sparta and Athens, thence some 70 poleis (around one-tenth of the total amount of Greek city-states) assembled and founded the Hellenic Alliance6. Sparta was appointed leader of the alliance army, with the famous King Leonidas being named Hegemon, or Commander-in-Chief of the league's forces. Athens however with her new great navy managed to become the leader of the alliance fleet, Themistocles its admiral.

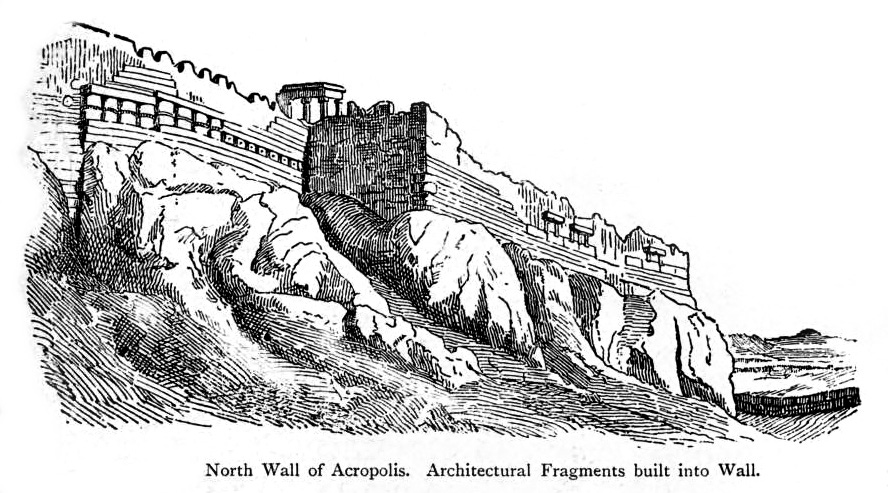

The Spartan-led coalition met the Persians at Thermopylae, 7,000 Greeks against 70,000-300,000 Persians. The narrow pass chosen as the location for battle by the Greeks so as to hinder the Persian number-advantage. The Greek force was defeated, but not before inflicting serious casualties on the Persians. Now Phocis, Bœotia (Thebes, allied from the beginning with Persia), and Attica were wide open to the Persian army. The people of Attica went southward to the Isthmus of Corinth, leaving the city and surrounding land empty, the Persians entered an empty Athens and sacked it, destroying everything on the Acropolis. The Athenians at this time lifted all exiles, Aristides then returned to his people and served under Themistocles in the allied fleet, while Leonidas was replaced by his nephew, Pausanias, as the new leader of the alliance army.

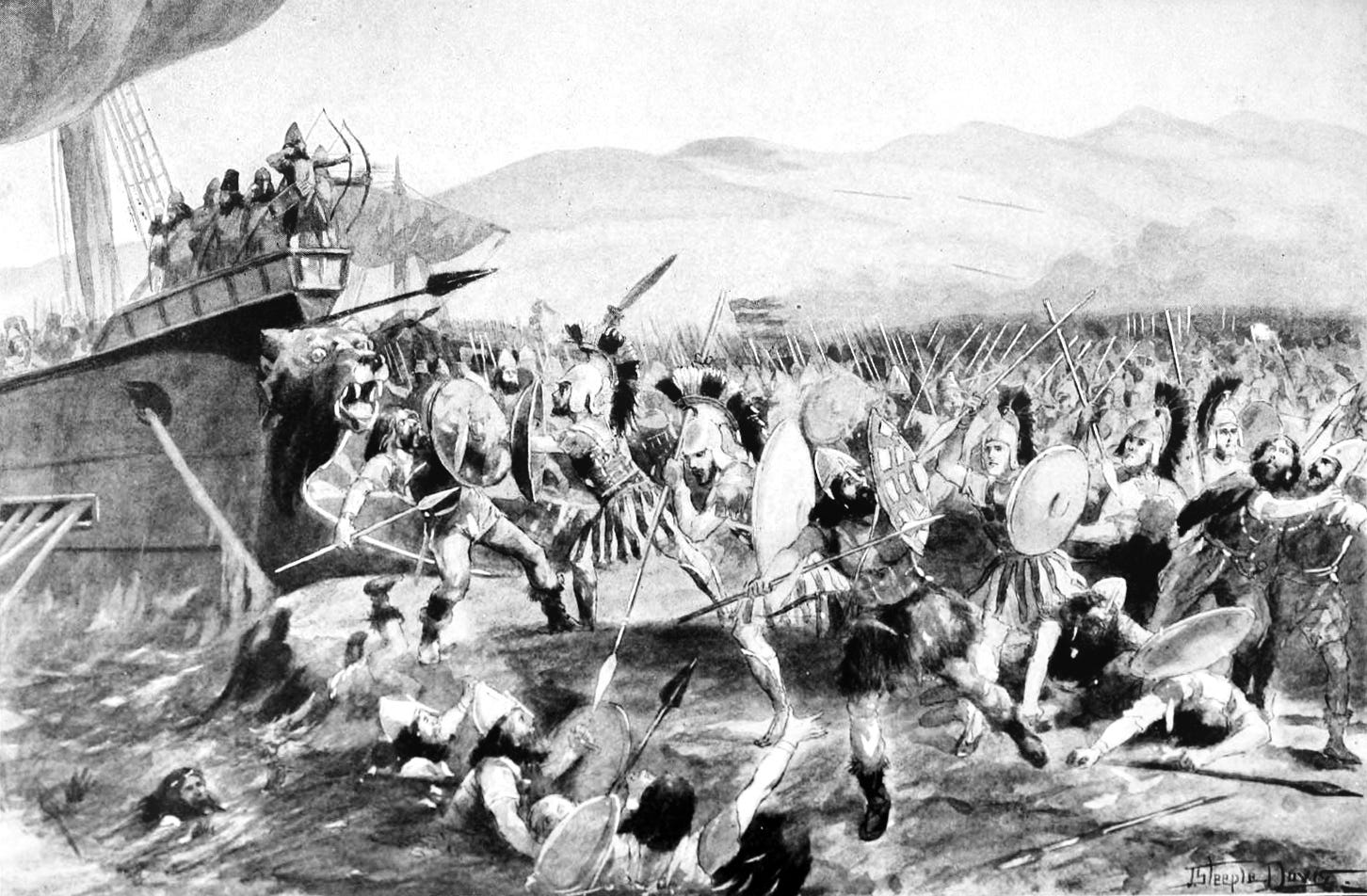

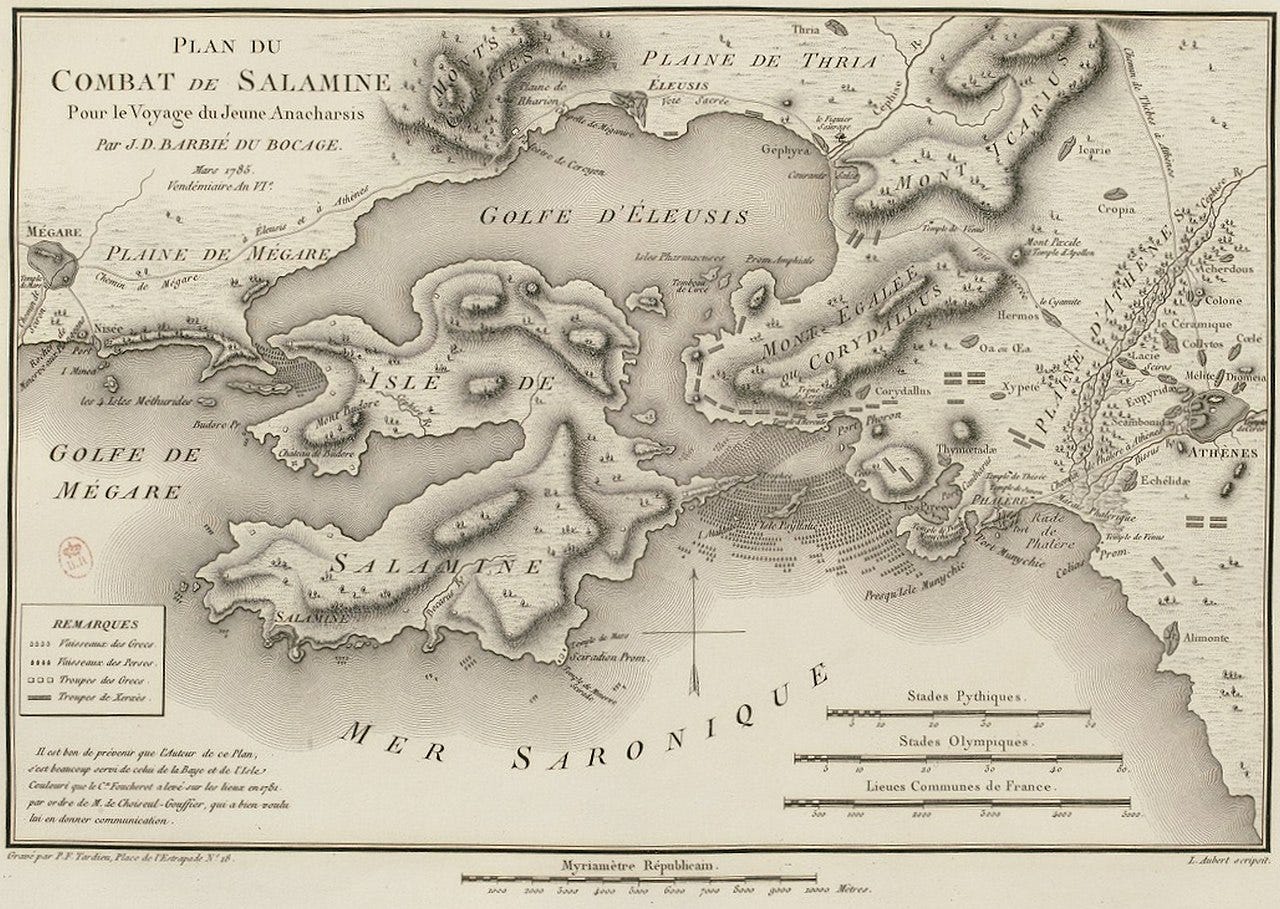

Xerxes sought a decisive naval confrontation to force the Greeks to begin negotiations, and the Greeks were willing to indulge him, in 480, at the Battle of Salamis.

Like Thermopylae’s intent, the narrow straits of Salamis would hinder the Persian numbers and turn them to a disadvantage. Some 370 Greek ships, 180 of which Athenian, versus 1,200 Persian vessels. Plutarch states that early into the battle the Persian chief admiral, Ariabignes, had been killed and his body thrown into the waters. The Greek fleet then split the Persian in two, and the Persians were defeated.

The Peloponnese, where the allied Greek army was stationed, was safe, and the Athenians returned to their burnt city for the winter, but the Persian general Mardonius marched on Athens once again, the populace fleeing, while the Athenian army was still in the Isthmus of Corinth, having not returned to their city. Athens was burned for a second time. Mardonius had wished for an open battle in the plains of Bœotia, eventually finding it, when the Spartan-lead alliance marched through Attica to rout the Persian army.

At the Battle of Plataea (479) in Bœotia the Persians were defeated for the final time in a land-confrontation during their second invasion of Greece. Persia lost access to Thebes her ally and Athens her capture. Plataea expelled the armies of Persia while another sea-battle, that of Mycale (479) near the island of Samos, destroyed the remainder of the Persian fleet.

After the conclusion of the war at Plataea and Mycale, the Athenians returned to their twice-ravaged city, the Spartans, however, forbid them from rebuilding the city walls, seeing that Athens could make a potential future rival already. Themistocles thus instructed the Athenians to build the city walls first and as fast as possible, while he and Cimon (son of Militiades) headed as ambassadors to Sparta. Playing for time for as long as they could. The Spartans rightly believed that Themistocles was lying about the walls, to that he answered that they should send an envoy to Athens to check for themselves, Themistocles instructing the Athenians to detain the Spartan envoy upon arrival.

Aristides then went to meet Themistocles and Cimon in Sparta to inform them of the walls being finished. The Spartans upon hearing of this sought to detain the Athenian embassy, but the Athenians reminded the Spartans of their own hostage (the envoy) back in Athens. The Spartans reluctantly let the embassy return to their city.

For that in strength unequal men cannot alike and equally advise for the common benefit of Greece. ‘Therefore,’ said he, ‘either must all the confederate cities be unwalled, or you must not think amiss of what is done by us.’

—Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War, 1.91

The rebuilt Athenian walls encompassed a greater area than just the city itself, and the Athenian port-city of Piraeus, also came to be defended, providing the inland-city with permanent sea-access.

The Hellenic alliance meanwhile continued to exist and went on the offensive, capturing many Persian holdings preceding the invasion, while the Ionian Greeks (those from 499) rebelled from the Persians once again and joined the alliance. Yet now the alliance was predominantly made up of the Ionian Greeks (in contrast to the leading Spartans, who were Dorians), and the issues of Spartan leadership came to light. Naval battles were incredibly important for repelling the invasion, yet naval contributions were not counted equally with those of land armies. Likewise did the Alliance become displeased with the new Hegemon, Pausanias, nephew of Leonidas, on account of his dictatorial nature and vanity. And so, in 478 B.C., an embassy of the many Ionian city-states approached the Athenian assembly, and asked them to take up the leadership of the Hellenic Alliance.

Born of the earth.

As per Burckhardt, many Greeks thought they literally sprung from the earth of their native soil.

This can be compared to the later Republican-era Roman Senate, which either rejected or approved legislation proposed by its members, in the latter case then warranting its presentation before the public assembly.

This was confused with another legend later on, which eventually gave rise to the story of an Athenian soldier running from Marathon to Athens without pause, announcing to the assembly “we have won!” and promptly dying of exhaustion thereafter.

Hence Sparta, the most aristocratic of the Greek city-states, always insisted on the importance of the army, while Athens, the most democratic, on the navy.

Not to be confused with the later League of Corinth (337 B.C.) engineered by Philip II of Macedon, also referred to as the “Hellenic League”.

![The Achaemenid Empire at its greatest territorial extent, under the rule of Darius I (522 BC–486 BC)[2][3][4][5] The Achaemenid Empire at its greatest territorial extent, under the rule of Darius I (522 BC–486 BC)[2][3][4][5]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fbucketeer-e05bbc84-baa3-437e-9518-adb32be77984.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F009ad2b2-772b-4e87-85ad-35107d9b2953_1920x1024.jpeg)